One of the benefits of the Covid-19 lockdown is the time it has provided to observe the local changes in the season as March segues into April and now May.

Virtual meetings provide the opportunity for actual breaks.

For the first time in perhaps three decades I can interrupt my writing or take breaks between (video)conferences.

There’s no longer a queue outside the door 😄 .

Instead of being cooped up in a windowless meeting room, I can turn off the video 1 and watch the cloud shadows chase across the hillside over the loch …

Primroses

… or step outside to look at the primroses and check up on the tadpoles in the pool.

It’s a liberating experience and one I suspect will actually increase both productivity and home-working once the lockdown ends. You return to the desk (assuming that you do return 😉 ) refreshed and revitalised.

How many employees will realise that the daily commute is not always necessary and there’s a better coffee machine at home?

How many companies will now realise they can reduce rented office space by 40% simply by allowing employees to work from home for two days a week?

Do we really need constant expansion of our transport network to move vast numbers of people there and back twice a day, every day?

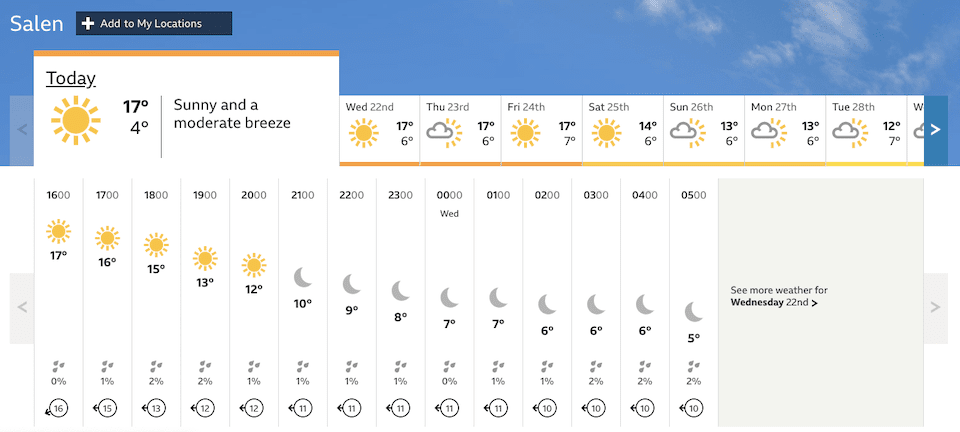

When I started writing this post we were into our third week of good weather. It proved too much of a distraction and so I’m finishing it a month later at the end of a wonderful seven weeks of glorious west coast spring.

Ardnamurchan weather, mid-April 2020

Which means that I’ve had loads of opportunities to watch the spring unrolling.

Summer visitors

I’m an enthusiastic but rather amateur birder. It’s been a great pleasure watching the migrants arrive in dribs and drabs over the last few weeks. The trees and bushes (I can’t bring myself to write rhododendron as there’s still too much of it about) are now filled with singing willow warblers and chiffchaffs, where they were largely silent a couple of months ago.

Chiffchaff

To the untrained eye (i.e. mine) these two birds look nearly identical.

Willow warbler

However, their songs are very distinctive and provide an unambiguous clue to their identification.

Song and call identification

I’ve taken advantage of lockdown to (virtually) attend a British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) training course on bird identification. This was good value and emphasised the importance of song/call recognition.

If you want to know what’s about you don’t need to actually see it to recognise it.

There’s an excellent catalogue of bird songs and calls at xeno-canto.org with most common birds represented (at least) dozens of times. Some calls have geographic variations and it’s worth using the advanced search to restrict the area to near where you are located 2.

Here are the aforementioned chiffchaff and willow warbler songs - two visually similar birds that are aurally totally different.

Incoming!

I usually try and make a note of the approximate arrival dates of migrants. It’s a good indication of how well advanced, or otherwise, the spring is. This year was the first time I had a chance to do this on the west coast of Scotland 3.

I know that both willow warblers and chiffchaffs had been around for several days before I properly became aware of them, so the dates for these two are a bit vague. Others are a little more certain, though seeing or hearing them depends upon being in the right place at the right time.

Cuckoos

Another bird with a really distinctive call. In 2020 I first heard a cuckoo calling on the 18th of April. The call carries a long distance and is completely unmistakable.

Since mid-April a number of birds have been calling in the area almost non-stop. You can hear them from first light until late into the evening. Despite the call being so distinctive and loud, the bird is wary and rather secretive.

Cuckoo

I’ve seen several birds along the Achateny road and they look remarkably like a sparrowhawk in size, shape and colouration. In particular the barred underparts are very hawk-like. However, in flight the wingbeat of the cuckoo is distinctive, with the wing rarely being raised above the horizontal, and the entire bird looking a bit more ‘pointed’.

Cuckoo mimicry and migration

The ‘mimicry’ of hawks by cuckoos was suggested to be an example of evolved mimicry by Alfred Russel Wallace in the late 19th Century. Essentially, cuckoos avoid predation by hawks because they look like hawks. The similarity may also influence host behaviour, for example by frightening or luring hosts away to facilitate egg laying.

Alternatively, it could be an example of convergent evolution i.e. both hawks and cuckoos have ended up looking alike to reduce the chances of detection by their victims, respectively, prey and hosts.

Many small birds, not just hosts for the cuckoo, respond in a similar way to both sparrowhawks and cuckoos 4 suggesting it’s not just birdwatchers who get confused by their appearance.

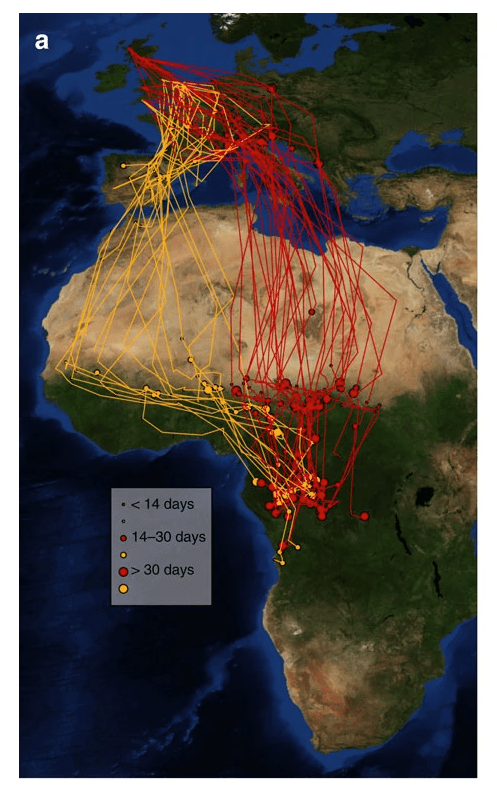

Cuckoo migration routes

The BTO have been tracking satellite-tagged cuckoos for several years. These studies show that the birds take easterly or westerly migration routes across the Mediterranean en route to sub-Saharan Africa. The westerly route, across Spain, is shorter but associated with higher mortality rates. This is possibly due to decreasing rainfall in Spain, with a concomitant drop in food availability.

The Scottish cuckoo population is thriving, with a 50% increase in numbers over the last decade. These birds take the easterly route to Africa down the spine of Italy. In contrast, the English cuckoo population has dropped about 27% over the same period (and 70% over the last 23 years) and the majority of these birds take the westerly route.

Blackcap

These small, rather attractive, warblers are widely resident in many more southern parts of the UK. There are reports of resident winter birds on Ardnamurchan but I haven’t seen them 5. However, the numbers increase significantly in spring - usually arriving in Scotland in late April - and the sort of scrubby woodland I’m surrounded by is now filled with singing males.

Blackcap

The blackcap is another bird that’s more often heard than seen. The poet John Clare termed the bird The March Nightingale reflecting the rich tones that characterise the end of a song that starts somewhat scratchily.

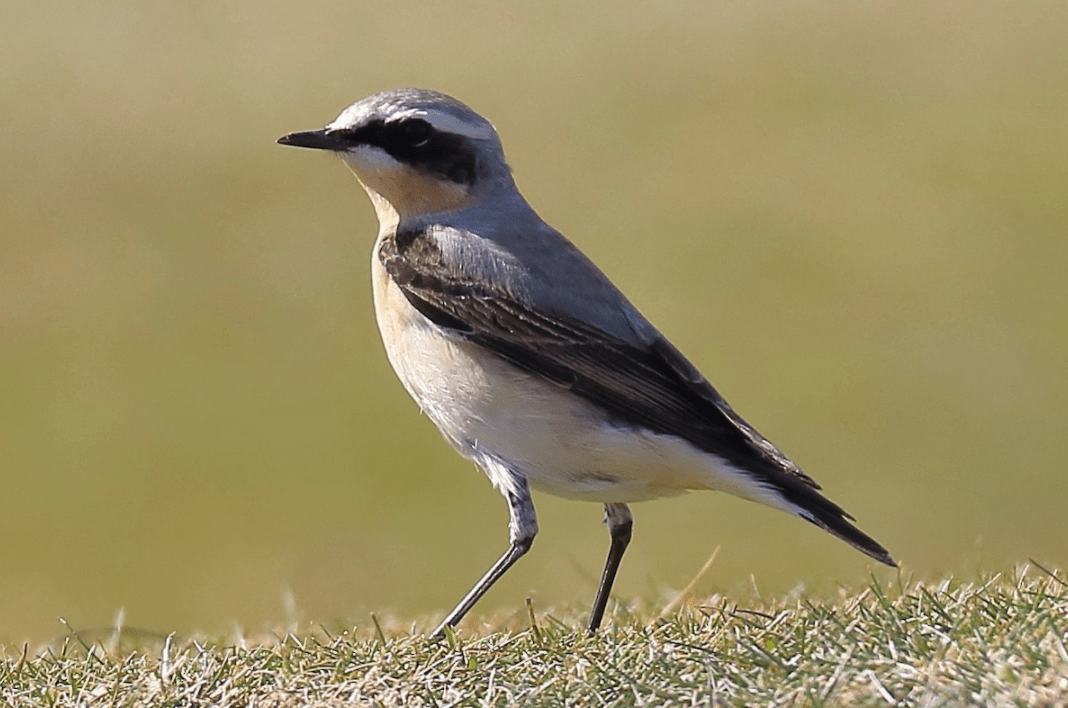

Wheatear

The wheatear is a bird of open moorland. As such, the earliest date I see them is dictated more by when I go out walking than anything else. Although the usual arrival time in Scotland is late March, I didn’t see one until the 17th of April while walking up the hill behind the house.

Wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe)

The wheatear is an attractive and very distinctive bird. In flight the white rump and black bar across the tail are unmistakable.

A couple of days later I was approaching Ben Laga and discovered this sad little pile of feathers on a mossy tussock. Included was one very distinctive black-tipped white tail feather.

Wheatear remains

This bird had flown all the way from sub-Saharan Africa to Ardnamurchan only to be eaten by a merlin 6 a few days after arrival.

Swallows, house martins and swifts

These are the classic summer migrants arriving in April and May.

House martins and swallows arrive in late April. Numbers appear to be lower this season, with very few in the immediate vicinity of the house. I saw both species for the first time on the 30th of April at Camas nan Gael, with more a couple of days later around the River Shiel.

Swifts don’t often get as far as Ardnamurchan and, if they do, they don’t breed here. In fact, they barely get past the Great Glen.

Notes

The word cuckoo is clearly onomatopoeic and is recognisable in Latin cucūlus, French coucou and Middle English, cucu or cuccu. The origin of the word meaning someone who is a bit crazy is not entirely clear. It probably dates back to the 16th Century and possibly originates from the endless repetition of the same phrase over and over.

If you are interested in the biology of the cuckoo, or cuckoos more generally, I thoroughly recommend Cuckoo: Cheating by Nature by Nick Davies, published in 2015 by Bloomsbury. ISBN-10 1408856565.

-

The picture’s breaking up … I’ll switch to audio only as the internet is a bit flaky this far west. ↩︎

-

Though it’s probably more important to only listen to the A-rated, best quality recordings. ↩︎

-

Last Spring was a write-off with silly amounts of work. ↩︎

-

N.B Davies & J.A Welbergen (2008) Cuckoo–hawk mimicry? An experimental test. Proc. R. Soc. B. 275:1817–1822. ↩︎

-

No guarantee whatsoever that they’re not about. ↩︎

-

An informed guess … I’ve seen them several times and this looked like a typical spot a merlin would pluck its prey. ↩︎